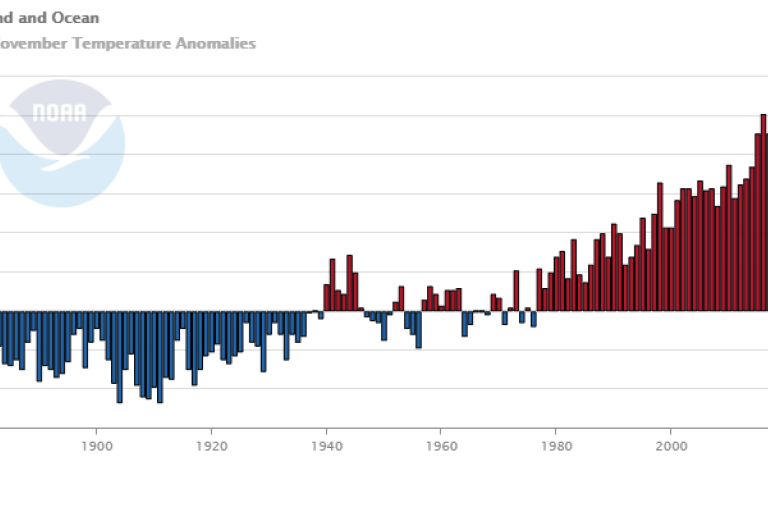

2020 closes a decade of exceptional heat

As 2020 draws to an end, it closes the warmest decade (2011-2020) on record, according to the World Meteorological Organization. This year remains on track to be one of the three warmest on record, and may even rival 2016 as the warmest on record. The six warmest years have all been since 2015.

As 2020 draws to an end, it closes the warmest decade (2011-2020) on record, according to the World Meteorological Organization. This year remains on track to be one of the three warmest on record, and may even rival 2016 as the warmest on record. The six warmest years have all been since 2015.

The exceptional heat of 2020 is despite a cooling La Niña event, which is now mature and impacting weather patterns in many parts of the world. According to most models, La Niña is expected to peak in intensity in either December or January and continue through the early part of 2021, according to a new WMO summary.

“Record warm years have usually coincided with a strong El Niño event, as was the case in 2016. We are now experiencing a La Niña, which has a cooling effect on global temperatures, but has not been sufficient to put a brake on this year’s heat. Despite the current La Niña conditions, this year has already shown near record heat comparable to the previous record of 2016,” said WMO Secretary-General Prof. Taalas.

WMO will issue consolidated temperature figures for 2020 in the month of January, based on five global temperature datasets. This information will be incorporated into a final report on the State of the Climate in 2020 which will be issued in March 2021, including information on selected climate impacts.

According to WMO’s provisional report on the State of the Climate issued on 2 December, all five datasets for the first 10 months of the year (until the end of October) placed 2020 as the 2nd warmest for the year to date, following 2016 and ahead of 2019.

The heat continued in November, based on monthly reports from the European Unions’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies and the Japan Meteorological Agency. This latest information classifies this November as either the warmest or second warmest on record.

The difference between the warmest three years is small and exact rankings for each data set could change once data for the entire year are available.

The temperature ranking of individual years is less important than long-term trends. Since the 1980s each decade has been warmer than the previous one. And that trend is expected to continue because of record levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide, in particular, remains in the atmosphere for many decades, thus committing the planet to future warming.

The average global temperature in 2020 is set to be about 1.2 °C above the pre-industrial (1850-1900) level. There is at least a one in five chance of it temporarily exceeding 1.5 °C by 2024, according to WMO’s Global Annual to Decadal Climate Update, led by the United Kingdom’s Met Office.

The Met Office annual global temperature forecast for 2021 suggests that next year will once again enter the series of the Earth’s hottest years, despite being influenced by the temporary cooling of La Niña, the effects of which are typically strongest in the second year of the event.

Note:

WMO uses datasets (based on monthly climatological data from observing sites of the WMO Members) developed and maintained by the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and the United Kingdom’s Met Office Hadley Centre and the University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit in the United Kingdom.

It also uses reanalysis datasets from the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts and its Copernicus Climate Change Service, and the Japan Meteorological Agency. This method combines millions of meteorological and marine observations, including from satellites, with models to produce a complete reanalysis of the atmosphere. The combination of observations with models makes it possible to estimate temperatures at any time and in any place across the globe, even in data-sparse areas such as the polar regions.