WMO steps up action on La Niña

The World Meteorological Organization has strengthened its support to governments, the United Nations, and stakeholders in climate sensitive sectors to mobilize preparations and minimize impacts of La Niña.

In October, WMO declared that La Niña has developed and is expected to last into next year, affecting temperatures, precipitation and storm patterns in many parts of the world.

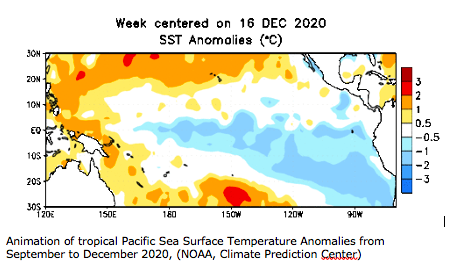

Since October, La Niña has continued to strengthen, as equatorial Pacific sea surface temperatures have cooled further. Many National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHSs) have reported that ocean and atmospheric indicators now indicate that the La Niña event has matured and, according to most models, is expected to peak in intensity in either December or January. Thus, Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology says that model outlooks suggest that La Niña is approaching its peak, with a likely return to neutral conditions during the late southern hemisphere summer or early autumn. The latest update issued by NOAA Climate Prediction Center and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society advised of 95% probability of La Niña continuing through to March 2021.

Impacts on weather patterns

La Niña is just one of a range of climatic drivers which affect our weather. Other examples include the Indian Ocean Dipole, Madden-Julian Oscillation and Southern Annual Mode. Forecasting the expected impacts of La Niña can therefore be complex. The strength of a La Niña event alone also does not necessarily correlate with the scale of shifts in rainfall or temperatures. No two La Niña (or El Niño) events are ever the same.

Seasonal forecasts, which incorporate all climatic drivers including La Niña, are providing a fuller indication on what global and regional climate patterns are expected. It is therefore important to consult the latest seasonal forecast available from National Meteorological or Hydrological Services (NMHS), Regional Climate Centers (RCC) or Regional Climate Outlook Forums (RCOF) for advice on what weather is forecast for the season ahead.

The WMO produces a Global Seasonal Climate Update (GSCU), based on a number of global seasonal forecast models run by WMO-accredited centres around the world. The update is intended as guidance for RCCs, RCOFs and NMHSs. It does not constitute an official forecast for any region or nation.

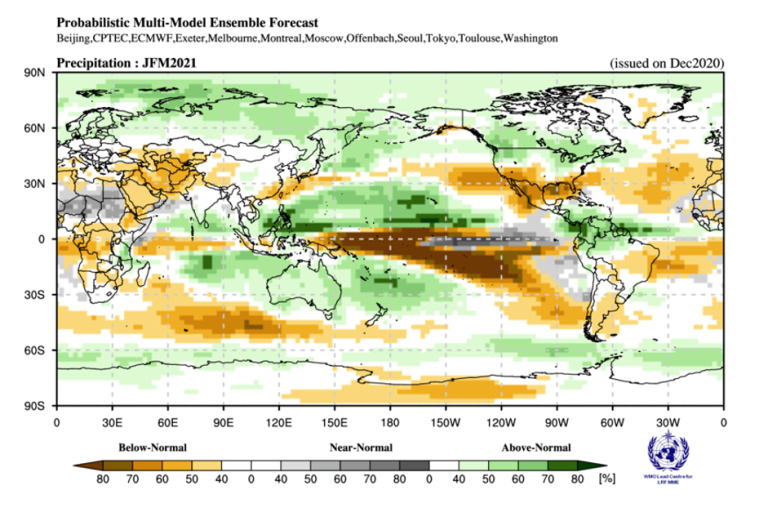

The latest WMO GSCU issued in December highlights those areas where temperature or precipitation anomalies may be experienced in the next three months (January, February and March).

One of the most prominent signals highlighted in the GSCU is the below normal rainfall signal across the Pacific. This region has already experienced a significant rainfall deficit in the last few months and there are concerns about drought impacts. Parts of central Asia, the southern North America, and parts of South America also have an increased probability of below normal rainfall. Each of these patterns are considered classical La Niña impacts.

Meanwhile, wetter than average conditions are forecast across Australia, especially along the east coast, where there has recently been severe flooding. The western equatorial Pacific and Central America are also more likely to see above average rainfall.

However not all areas are so clearly following the typical La Niña pattern. For example, there is no strong signal apparent over southern Africa, which typically sees wetter conditions with La Niña.

Impacts on society

To make sure that the true value of these forecasts is realised, it is important that the weather and climate community work with climate sensitive sectors to translate this risk-based information into action. WMO Members are working with health, transport, energy, agriculture and disaster risk management entities, to name just a few, to achieve this.

WMO has supported a number of regional La Niña briefings, organised by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the Food and Agriculture Organization in recent weeks. The briefings provided an opportunity to discuss the implications of the seasonal forecast and devise effective mitigation strategies. To date regional briefings have been held for the Pacific, South East Asia and East Africa.

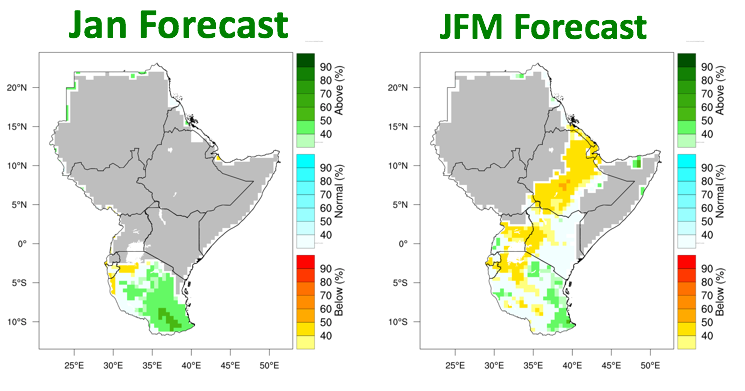

East Africa Briefing

In East Africa, a La Niña briefing was organized in conjunction with the Food Security Network Working Group to assess the possible food security

impacts. The IGAD Climate Prediction and Application Center (ICPAC), led the briefing, describing both the seasonal forecast over the next three months, as seen below, and an outlook for the next important rainy season in March-May 2021. ICPAC highlighted a mixed outlook that is currently forecast for March-May, but stressed that the skill of such forecasts, with a five-month lead time, is very low. Interested parties should continue to check updates for the latest information.

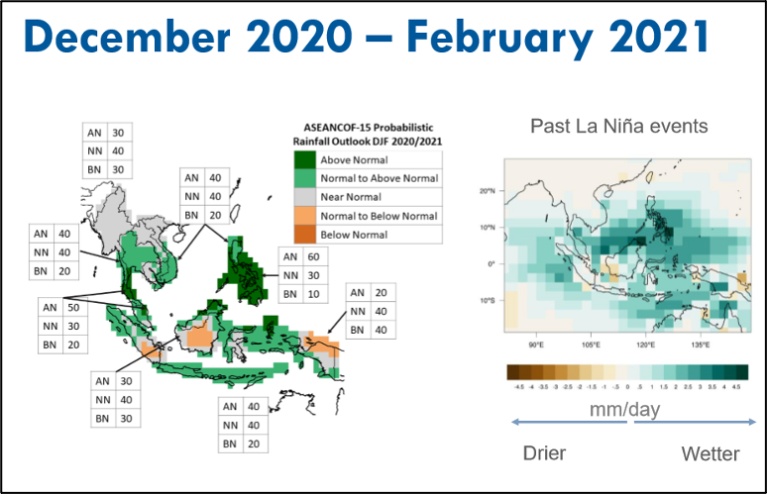

South East Asia Briefing

South Asia is expected to see a typical La Niña weather response over the next three months, with wetter than average conditions affecting most parts, particularly the Philippines, with an increased risk of flooding and landslides. At the South East Asia Regional Humanitarian Partners La Niña briefing, the ASEAN Specialised Meteorological Centre (ASMC) provided ASEAN Climate Outlook Forum analysis below, to highlight the regional details of the latest forecast.

Pacific Region Briefing

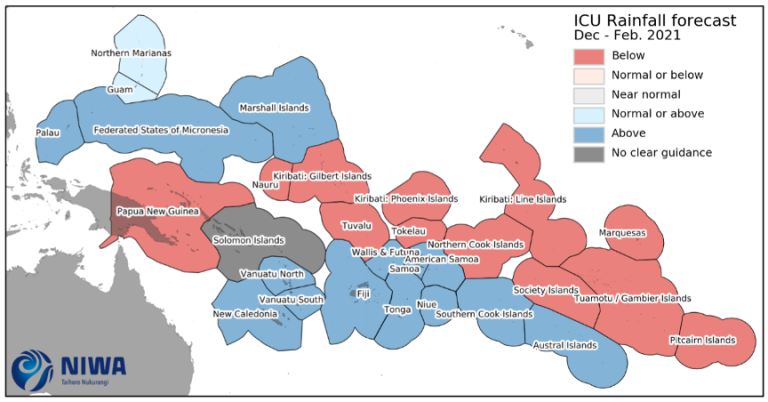

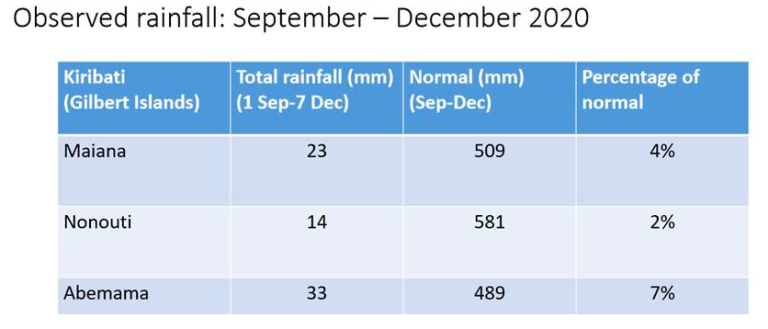

In the Pacific Region, New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) presented the precipitation map below, provided through the Pacific Islands Climate Outlook Forum (PICOF). It highlights the probability of below normal rainfall across a large area of the central Pacific and reflects the output provided by the GSCU. The briefing also highlighted the severely below average rainfall that has been recorded so far. For example, according to the Pacific Island Climate Outlook Forum, Kiribati has received less than 10% of its average rainfall over the past three months, raising water security concerns (see table right, below).

- WMO Member:

- Australia ,

- United States of America