The cryosphere raises a “red flag”

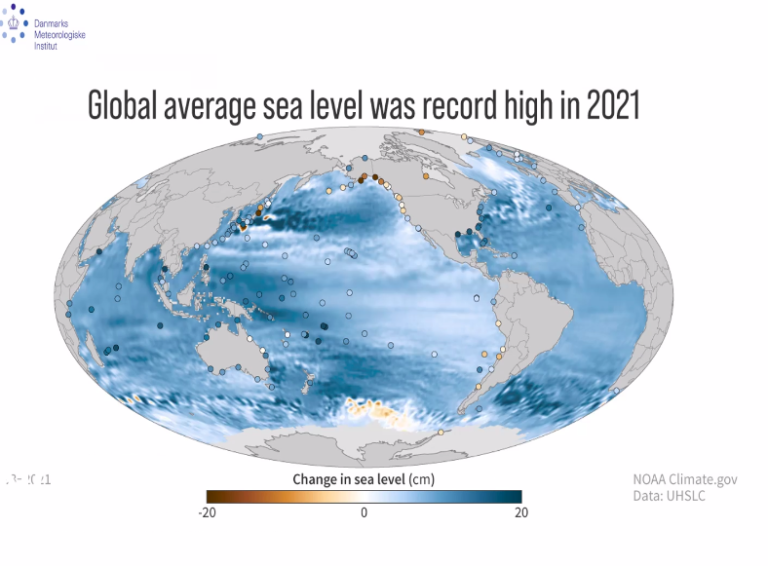

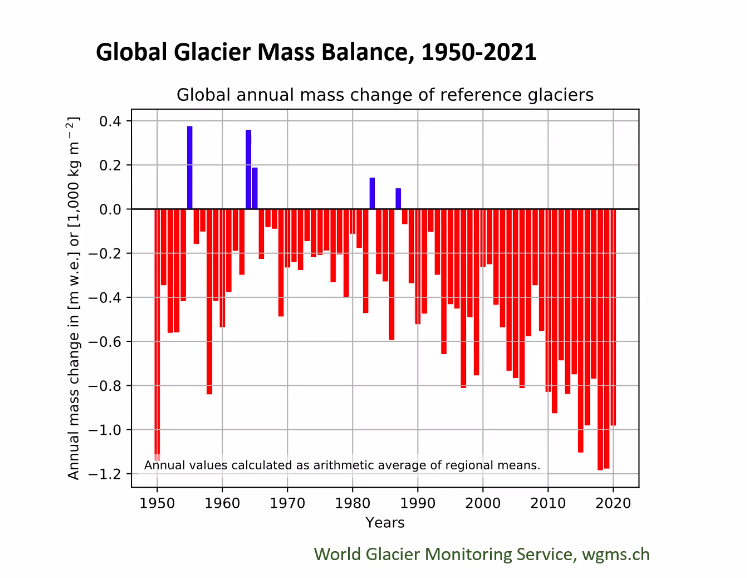

Ice sheet loss in Greenland and parts of Antarctica is gathering pace and is largely irreversible. The resulting acceleration in sea level rise is a major threat to billions of people in coastal regions. Glacier retreat in high mountain areas brings the risk of long-term water scarcity in densely populated parts of the world.

Ice sheet loss in Greenland and parts of Antarctica is gathering pace and is largely irreversible. The resulting acceleration in sea level rise is a major threat to billions of people in coastal regions. Glacier retreat in high mountain areas brings the risk of long-term water scarcity in densely populated parts of the world.

“We’ve raised the red flag for the cryosphere,” WMO Deputy Secretary-General Dr Elena Manaenkova said in summarizing the latest scientific knowledge and the physical climate change signs.

Underlining the concern, a broad coalition of 18 governments — led by the two polar and mountain nations of Chile and Iceland — joined together at COP27 to create a new high-level group ‘Ambition on Melting Ice on Sea-level Rise and Mountain Water Resources’. The “AMI” group aims to ensure impacts of cryosphere loss are understood by political leaders and the public, and not only within mountain and polar regions, but throughout the planet.

“Climate change already has caused dramatic changes in the global cryosphere, Earth’s snow and ice regions. Severe impacts are already occurring in relation to water shortages from shrinking glaciers and snowpack; global sea-level rise due to loss of ice from ice sheets, glaciers and ocean warming; and landslides triggered by permafrost thaw. Lives and livelihoods are threatened by, and some already lost from, these changes. Indigenous peoples in both the Arctic and mountain regions have been among the earliest affected,” said the declaration.

“Today’s grave impacts from cryosphere loss pale, however, in comparison to what the latest science tells us would be increasingly severe and widespread impacts at higher levels of global warming,” said the statement.

Repeated interventions and presentations at the UN climate negotiations, COP27, said that meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement to keep temperature increase to 1.5°C to 2°C above pre-industrial levels will determine the fate of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets and the high mountain “Water Towers” of the world. And thus, the future of the large parts of the planet.

In the face of the mounting threats, greater international coordination is needed to develop plausible scenarios for future changes and their impacts, and to translate global scientific knowledge into localized information that supports adaptation strategies for people and regions most at risk.

State of Climate

Arctic sea-ice extent was below the long-term (1981-2010) average for most of the year. The September extent was 4.87 million km2, or 1.54 million km2 below the long-term mean extent. Antarctic sea-ice extent dropped to 1.92 million km2 on 25 February, the lowest level on record and almost 1 million km2 below the long-term average.

2022 took an exceptionally heavy toll on glaciers in the European Alps, with record-shattering melt. The mountains in the Hindu-Kush region – the so-called Third Pole – have also suffered. The Greenland ice sheet lost mass for the 26th consecutive year.

Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets

The implications of the rapid change were examined at a side event organized by WMO on “The loss of Antarctica and Greenland ice sheets in a warming climate – bridging between science and action.”

The session provided an overview of recent scientific results on the observed and projected changes on Greenland and Antarctica and their impacts at global level, on sea level rise and the global climate system, as a whole. It stressed the need for sustained access to relevant observations data, and for user-driven services to translate science into local action and support adaptation – often in tropical zones far away from the Poles.

“Sea level rise is not just something we will feel in 100 years. Every millimetre and centimetre makes a difference,” said Prof Shawn Marshall, Department Science Advisor, Environment and Climate Change Canada.

“As the centuries go on, we are talking about tens of meters of sea level rise and it’s something we need to prepare for and adapt to.”

Dr. Adrian Lema – Director, National Climate Research Centre of the Danish Meteorological Institute, said that some of the changes in the cryosphere were taking place much earlier than expected – this century rather than next century.

Greenland’s highest tip, the Summit Station, had rain for the first time in July 2021. And it rained on the ice sheet this September – rather than snow.

“Greenland is like a bank account. When snow falls you put money in the bank, when ice melts or breaks off, you take money out of the bank. For the past 26 years in a row, there is less money in the bank compared to the previous years,” said Dr Lema.

Sleeping Giant

In Antarctica, the ice loss is currently largely confined to the West Antarctic ice sheet which – like the Arctic – is warming more rapidly than the global average and this is one of the factors behind accelerating sea level rise.

East Antarctica is by far the world’s biggest ice sheet, containing water which is the equivalent to around 50 meters of sea level rise. And so far, the East Antarctic ice sheet has seen very little surface melting, according to Dr Chris R Stokes, a professor in Sea Level, Ice and Climate at Durham University in the United Kingdom.

“So far that ice sheet seems to be okay. East Antarctica is the huge sleeping giant we don’t want to wake up,” said Dr Stokes. “But we have been ignoring this ice sheet for too long and it’s something we need to start looking at now. History tells us that sea level rise from ice sheets can be very, very rapid,” he said.

Small islands on the frontlines

The impact is global. Small island developing states are on the frontlines.

Albert Martis, head of the meteorological of Curacao, said the Caribbean was “ground zero.”

Willhelmstadt, the capital of Curacao and a UNESCO World Heritage site, risks being inundated. Hence the need for adaptation strategies now.

“We don’t need to wait to 2050 to be flooded. It is already happening now,” he said.

South-West Pacific delegates also sent a heartfelt message plea for urgent action.

“Our islands are sinking. It’s not a joke,” 'Ofa Fa'anunu, head of Tonga’s national meteorological and hydrological service said at the launch of the State of the Climate in the South-West Pacific launch on 17 November.

“We are at 1.1°C now above the pre-industrial era and we are already struggling. It’s hard to imagine what’s going to happen at 1.5°C and above,” he said.