The Role of the Hydrometeorological Service in the Information Economy

- Author(s):

- By Charles Ewen, Met Office

As a professional technologist working within a deeply scientific domain, I have spent more time than one might expect explaining exponential growth. In the past, this has been mostly through analogy; from grains of rice on a chess board to bacteria on a petri dish. In these difficult and uncertain times, I am finding that I am having to explain this much less. Lamentably, the COVID-19 pandemic has made us all very much familiar with the consequences that exponential growth can have on our society. The issues do not appear early on, but instead, at the point at which large numbers start to double.

In 1965, Gordon Moore, the co-founder of Intel, wrote his seminal article for Electronics magazine. As frequently quoted, he commented upon “component cramming” – now synonymized with the number of silicon gates that can be squeezed onto a silicon wafer. But other aspects of the article were even more insightful: Moore highlighted that component cramming would lead to [exponentially growing] “complexity for minimum component costs.” “Technology-driven change” is something we have all become accustomed to over the last few decades; however, it is still easy to underestimate the dramatic effect of exponential growth on large numbers.

The Rise of the Information Economy

In their insightful 2014 book, The Second Machine Age, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee postulated that mankind were at the cusp of an economic and social change comparable to the industrial revolution with mind, as opposed to muscle, as the theme of change. They suggested that this mind revolution would happen significantly faster than the 100 years or so that it took the Industrial Revolution to transform our world. Less than seven years on, it looks as if they were right. The companies that now dominate global earnings can attribute their spectacular growth, at least to some degree, to being in the “information” business.

At the Met Office, the Executive teams have put a considerable amount of time and effort into understanding the “Information Economy,” the role that we already play, and what we might do differently to deliver the maximum public good. This has been challenging as, in many ways, organizations like the Met Office have always been in the information business. We have also been at the forefront of many of the technological implications of Moore’s Law, in terms of running very highly-scaled technology platforms, complex observation platforms, and sophisticated simulations. Indeed, it is also possible to characterize applied science or operational meteorology as being in the information business, as ultimately it is all about generating new knowledge or assisting decision-making.

Another factor of the developing information economy is that as there are now more people in the information business, as well as many more in the predictions business. One of the core premises of machine learning is the development of algorithms that are able to identify patterns in datasets that represent a system. Assuming that the system will continue to behave in the future as it has done in the past, this creates a predictive capability. This is well documented elsewhere and is leading to the rapid growth of organizations that are, in some way, in the predictions business. I will refrain from commenting here upon the longer-term possibilities of machine learning augmenting sophisticated physics-based models. That debate aside, machine learning will certainly have a significant impact on the end-to-end mission of helping people make better decisions. This is another example of the new ways in which National Hydrological and Meteorological Services (NMHSs) will need to interact with the information economy as distinct from the weather enterprise.

|

|

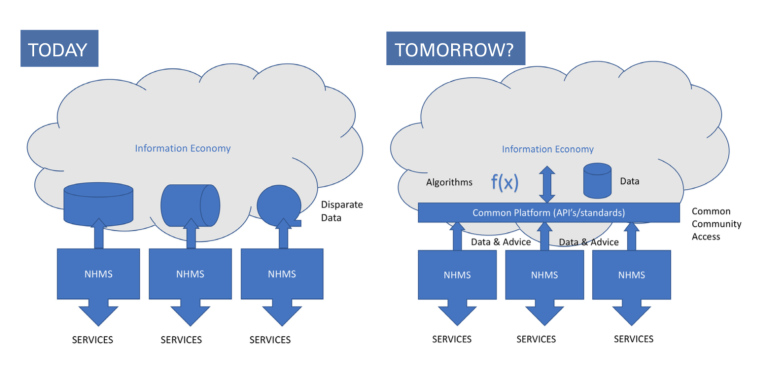

Today: Each NHMS pushes data of disparate approaches into the internet to be made available to the information economy. Combination of the data verbosity and complexity as well as variety approaches and formats makes it hard or impossible for the information economy to use. This tends to be the cumulative effect of 'the weather enterprise' approach (left). Tomorrow?: Via API’s and agreed methods and standards, the NHMS community make data and advice (forecasts, warnings, etc.) available on demand. This limits the verbosity impacts over bulk push and also allows complexity to be addressed by offering a computational capability allowing user-driven processing on Public Cloud (right). |

Similarly, the effect of the exponential growth on the affordable availability of high-capacity and high- capability infrastructure is also very significant. No longer is scaled infrastructure the sole privilege of those with access to, and the ability to manage, large amounts of capital. Public Cloud further accelerates technology-driven change by allowing small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) – and talented individuals – to access, process, combine, analyse and use vast quantities of data. This creates new possibilities for collaboration in all areas of our organizations but also demands that we make our data “useful” to these new entities. This is probably not best achieved by simply “fire-hosing” vast quantities of disparate, complex data onto the Internet.

|

| Weather and climate supercomputers at the Met Office. |

Another challenge for the Met Office has been to re-think concepts such as “the weather value chain” and “the weather enterprise.” Real-world decisions are typically not solely based upon the future state of the atmosphere, but rather the impact that this is likely to have on our everyday lives. These insights can often only be made with other data that is not weather, water, or climate-related. For many important decisions, such as investment in flood defences or choosing the safest aircraft route, weather and climate are the dominant factor, but in most cases, there are many other contributing factors. The verbosity and complexity of modern EPS (Ensemble Prediction System) simulations also mean that it is not realistic, affordable, or even possible to distribute the data within a useful timeframe. In the words of Ray Kurzwell, we have reached the “second half of the chessboard.” This infers the need for an open-platform approach that facilitates integration with data and processing algorithms from other areas of the information economy. Ideally, this would include the ability to operate on all datasets at the point of generation. The more traditional notion of the widespread distribution of simulation data for exploitation by third parties (and the consequential realization of public good) does not stand up to the test of (very) big data. This potentially controversial outlook is based upon the premise that” the weather enterprise” is very rapidly being superseded by the wider “information economy.”

How to think differently

All NMHSs are familiar with the wearing of many (or at least more than one) hats. With very few exceptions, Met Services are part of their domestic government and also part of an international community, orchestrated by the WMO (so that’s two). Many Met Services also have research programmes and/or have global or limited-area model programmes at various geospatial and temporal scales and all run observations programmes. All also have some interaction with the private and third sectors, some at a limited scale and others at quite a large scale. This multi-faceted nature is typically long-term and slow-moving. As such, the organisation is very adept at switching context (changing hats!), and thinking, planning and acting from different perspectives. At the Met Office, we actively decided to re-imagine (think) and plan from the perspective of a “big data company within the information economy,” so what did that tell us to do differently? Some of our summary findings:

- The information economy is intrinsically global. Just like weather and climate, it does not respect geo-political boundaries and also targets local impact. Herein lies an opportunity and a major dilemma for the hydrometeorological contribution to the information economy. Today, whilst there is a strong community that has been phenomenally successful at collaboration in many areas, but it is very hard (or even impossible) to meaningfully interact with us as a single entity/capability/source of truth. This is mostly because we do not offer a single and unified method or point of access.

- The data that we share publicly is often not suited, nor presented, in a manner that is useful to non- experts that need authoritative information to assist with real-world decision-making. These data are essentially “weather forecasts” (or climate predictions).

- Forecasts or predictions are fundamentally different to data that describe “facts” (e.g. observations) – they are essentially “opinions.” We need to know where or who they come from, when and how they were made so that we can interpret and properly use them. In the development of policies and strategies, the word “data” is an oversimplification, since the treatment of an “opinion” is very different to the treatment of a “fact” – however well-qualified it is!

- There are significant risks associated with treating a “prediction” as “data” in isolation and without expert hydrometeorological or climate science interpretation and advice. For significant decision- making, it is critical that expert guidance and advice is available to the information economy.

This is not the place to decompose these findings, nor to lay out how the Met Office intends to respond to this new perspective. The new Met Office purpose is “helping you make better decisions to stay safe and thrive.” This seemingly innocuous change of purpose has significant implication when coupled with the realization that we need to play a central role in the rapidly developing information economy. Suffice to say that it makes collaborative structures such as the WMO, EUMETNET, EUMETSAT, and all lthe other organisations that we collaborate with when wearing one of our familiar hats, more relevant and important than they have ever been. It also means trying out some new hats for size in the way that we work with public, third and private sectors. This will be critical to ensure that our community continues to develop the maximum possible social value from the important work that we all undertake.

In A sociology of our relationship to the world (2019), Hartmut Rosa argues that society has ended up in a paradoxical state of “frenetic standstill” – where everything is constantly moving and yet nothing really ever changes. According to Rosa, this is because the rate of technological, economic and social change is now so fast that we are unable to control or manage these spheres through the slow processes of achieving consensus. It is with this caution that, as a community, we must be open to wearing some unfamiliar hats and identify the means through which our community can shift to become a core element of the emerging information economy, rather than being superseded by it.