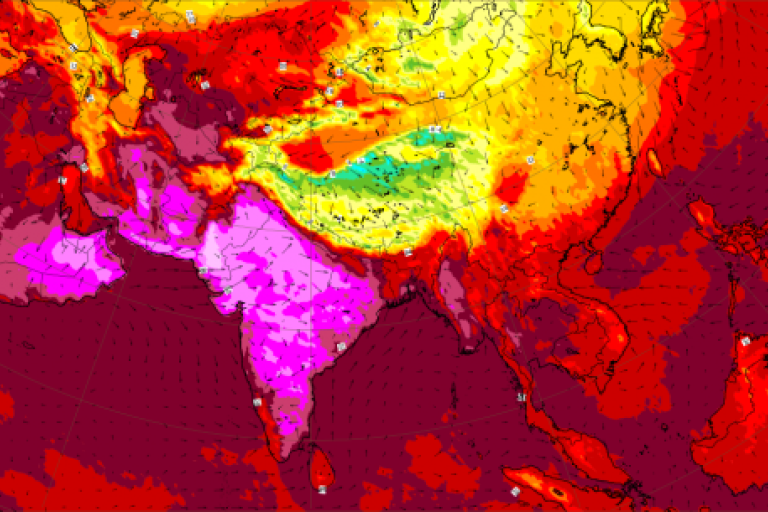

Climate change made heatwaves in India and Pakistan "30 times more likely"

Extreme heat which gripped large parts of India and Pakistan was made 30 times more likely because of climate change, according to a new rapid attribution study by climate scientists.

The heat was prolonged and widespread and coupled with below-average rainfall, impacting hundreds of millions of people in one of the most densely populated parts of the world. The national meteorological and hydrological departments in both countries have working closely with health and disaster management agencies to save lives, in line with the WMO drive to strengthen early warnings and early action and to implement heat-health action plans.

On 15 May, the India Meteorological Department said that numerous observing stations reported temperatures of between 45°C (113°F) and 50°C (122 °F). This followed a heatwave at the end of April and early May, at which temperatures reached 43-46 °C.

Temperatures also hit 50°C in Pakistan. The Pakistan Meteorological Department said that daytime temperatures were between 5°C and 8°C above normal in large swathes of the country. The hot, dry weather impacted water supplies, agriculture and human and animal health. In the mountainous regions of Gilgit-Baltistan and Khyber Pakhtunkwa, the unusual heat enhanced the melting of snow and ice and triggered at least one glacial lake outburst flood.

"The full health and economic fallout, and cascading effects from the current heat wave will however take months to determine, including the number of excess deaths, hospitalisations, lost wages, missed school days, and diminished working hours. Early reports indicate 90 deaths in India and Pakistan, and an estimated 10-35 percent reduction in crop yields in Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Punjab due to the heatwave," said the report by World Weather Attribution.

"It was the early, prolonged and dry heat that made this event stand out as distinct from heatwaves occurring earlier this century,” said the study. It involved scientists from India, Pakistan, the Netherlands, France, Switzerland, New Zealand, Denmark, United States of America and the United Kingdom, who collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the heatwave.

Because of climate change, the probability of an event such as that in 2022 has increased by a factor of about 30, said the study.

- The same event would have been about 1C cooler in a preindustrial climate.

- With future global warming, heatwaves like this will become even more common and hotter. At the global mean temperature scenario of +2C such a heatwave would become an additional factor of 2-20 more likely and 0.5-1.5C hotter compared to 2022.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in its Sixth Assessment Report, said that heatwaves and humid heat stress will be more intense and frequent in South Asia this century.

India’s Ministry of Earth Sciences recently issued an open-access publication about climate change in India. It devoted a whole chapter to temperature change.

The frequency of warm extremes over India has increased during 1951–2015, with accelerated warming trends during the recent 30 year period 1986–2015 (high confidence). Significant warming is observed for the warmest day, warmest night and coldest night since 1986.

The pre-monsoon season heatwave frequency, duration, intensity and areal coverage over India are projected to substantially increase during the twenty-first century (high confidence).

The heatwave was triggered by a high pressure system and follows an extended period of above average temperatures.

India recorded its warmest March on record, with an average maximum temperature of 33.1 ºC, or 1.86 °C above the long-term average. Pakistan also recorded its warmest March for at least the past 60 years, with a number of stations breaking March records.

In the pre-monsoon period, both India and Pakistan regularly experience excessively high temperatures, especially in May. Heatwaves do occur in April but are less common. It is too soon to know whether new national temperature records will be set. Turbat, in Pakistan, recorded the world’s fourth highest temperature of 53.7°C on 28 May 2017.

Both India and Pakistan have successful heat-health early warning systems and action plans, including those specially tailored for urban areas. Heat Action Plans reduce heat mortality and lessen the social impacts of extreme heat, including lost work productivity. Important lessons have been learned from the past and these are now being shared among all partners of the WMO co-sponsored Global Heat Health Information Network to enhance capacity in the hard hit region

The South Asia Heat Health Information Network, SAHHIN, supported by GHHIN, is working to share lessons and raise capacity across the south Asia region.

The city of Ahmedabad in India was the first South Asian city to develop and implement a city-wide heat health adaptation in 2013 after experiencing a devastating heatwave in 2010. This successful approach has been expanded to 23 heatwave-prone states and serves to protect more than 130 cities and districts.

Pakistan has also made strides towards protecting public health. In the summer of 2015, a heatwave engulfed much of central and north-west India and eastern Pakistan and was directly or indirectly responsible for several thousand deaths. That acted as a wake-up call and led to the development and implementation of the Heat Action Plan in Karachi and other parts of Pakistan.

Heat Action Plans at the city, state/provincial, or federal level bring a range of authorities and actors together to better understand and more effectively predict, prepare, and respond to extreme heat risks. Heat Health Warning Systems are an integral part of these and are provided by National Meteorological Services. More information and examples of Heat Action Plans can be found at https://ghhin.org/take-action/

Civil society, such as the Red Cross Red Crescent Society and the Integrated Research and Action for Development (IRADe), also play a critical role, deploying lifesaving communications and interventions to vulnerable communities. Typical plans make sure the targeted intervention is a right fit and designed for the heat vulnerable population of a city. It first identifies the heat hotspots of the city, locates the vulnerable populations in these pockets, and assesses the nature and status of their vulnerability to extreme heat. The action plans have tremendously helped in reducing excess mortality.