Acting early in times of a pandemic: The challenge of staying ready for extreme-weather events during COVID-19

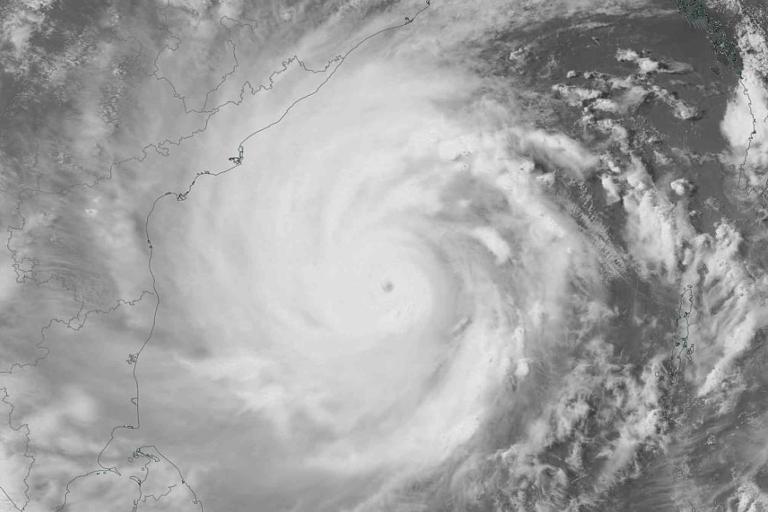

Extreme events do not stop for a pandemic. This has been illustrated vividly by the impacts of Cyclone Harold in the Pacific, tropical storm Amanda in El Salvador, the Zagreb earthquake in Croatia, and super Cyclone Amphan in Bangladesh and India. Many countries experiencing rising Covid-19 infection rates are susceptible to natural hazards. Many countries where humanitarian organizations implement anticipatory approaches to humanitarian action—like Forecast-based Financing[1] (FbF)—are currently under some type of lockdown or applying Covid-19 mitigation measures. Vulnerable populations in these countries (will) find themselves exposed to the dual, or even triple, impact of Covid-19 and disasters like floods, landslides, cyclones, droughts, earthquakes, locust infestations, or conflicts.

As humanitarians, we are obliged to protect populations at risk from extreme events, at the same time it is essential that we avoid exposing vulnerable populations to further harm from possible infection. As many FbF and anticipation countries are entering seasons where extreme weather is likely, we face complex questions regarding how to balance the ongoing work to mitigate Covid-19 infections with the need to protect the population from approaching disasters:

- Is it possible to take early action while travel and other restrictions are in place, especially for hazards for which we have short lead-times and where quick movement of staff and relief items is of the essence?

- What type of early actions are indispensable, even if implementation could increase the risk for Covid-19 infection?

- How do we address that implementing early actions could put volunteers’ health at risk? How do we minimize those risks?

- How can we maintain physical distancing during distributions or evacuations?

- Can we expect local branches and authorities to implement early actions without assistance from their headquarters or central offices?

The current situation means that existing plans, Early Action Protocols, Standard Operating Procedures, and contingency plans need to be rethought, including planning what types of early actions can still be implemented and what modalities could look like that help mitigate the risk of the extreme weather without increasing the risk of Covid-19 transmission.

In the Red Cross Red Crescent movement, different National Societies are currently looking at their Early Action Protocols, deciding which actions are feasible and which are not, which ones can be adapted to mitigate the risk of spread in Covid-19, and how. According to Valeria Drigo of Global Network of Civil Society Organisations for Disaster Reduction (GNDR), other organisations are doing the same: “GNDR members in various countries (e.g. Pakistan and DRC) are working with the local authorities to review and update their contingency plans and SOPs to “pandemic-proof” future disaster responses.” To do this, a good understanding of the compound risks is necessary, which is why local GNDR partner organizations—such as those in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan that were recently affected by dam break and mud flows—advocate for governments to intensify their local risk assessments.

In the past weeks, practitioners of anticipation in different countries have reflected on these questions, and in countries like Philippines, Vanuatu, and Bangladesh, their decisions have already been put to the test.

Can we take action with the different restrictions in place?

The implementation of early action in most cases will depend on the mobility of staff and volunteers, their access to communities at risk, and the availability of relief items and will also pose challenges for maintaining contact restrictions and physical distancing. In countries with lock downs or similar Covid-19 restrictions in place, most of these factors would be compromised, if early actions such as evacuations were to be carried out without adaptations. When FbF project managers were asked during an April meeting whether implementing early actions as initially planned would be possible, they responded, “if restrictions are maintained and we don’t adapt the EAPs, then no, we cannot act”.

Since April, the events of Cyclone Harold in the South Pacific and Cyclone Amphan in Bangladesh have shown that when a hazard presenting immediate risks to life and health of the population approaches, governments will relax restrictions so that humanitarian actors such as the Red Cross can act to save lives and evacuate. That is good news. However, in these cases the threat was imminent, the potential harm was obvious, and early actions were primarily associated with evacuation. Whether governments will lift restrictions to allow for early action when the threat is less visible remains to be seen. Jerome Faucet, FbF project manager for the German Red Cross in Vietnam says: “The government is increasingly aware of the risks associated with heatwaves, very interested and keen to engage with us on early actions. But heat waves are not perceived to be as dangerous as other hazards yet. So, I am not sure, if we have a warning of extreme heat this summer, if we can really act.” As Jerome adds, independent of whether early actions are authorized, the National Society needs to assess how to implement them so that they do not replace one health threat with another. His team is currently considering how to operate cooling centres — a key early action in Vietnam — without increasing Covid-19 transmission; the idea of cooling buses was abandoned for the duration of the pandemic because it could not be adequately adapted.

For Typhoon Ambo in April, the Philippines Red Cross (PRC) did not activate its Early Action Protocol, as the trigger was not reached at the pre-agreed decision time of minus 72 hours; thus, early actions such as pre-harvesting of abaca trees and shelter strengtheningwere not taken. The government might have authorized them; however, travel restrictions and lack of flights would have meant that local Red Cross chapters could not count on assistance from the PRC headquarters. The team has since adapted their Early Action Protocol for Typhoons to include additional measures to avoid Covid-19 transmission and to comply with restrictions, e.g. by equipping harvest workers and volunteers with PPE and arranging additional transport to stay in line with regulations on maximum number of persons per vehicle. Nevertheless, even with these adjustments in place, the Philippines team cannot say for sure whether they will be able to act when a trigger is reached. Restrictions vary by province and community and the final authorization of early actions lies with local authorities. This means whether the activation of an Early Action Protocol is possible will have to be established case-by-case. The Philippines government has adopted an interim humanitarian protocol, regulating how humanitarian assistance can be provided under Covid-19 restrictions, but these are not adapted to the operational needs of early action and early response. For example, they require all beneficiaries to be pre-identified and beneficiary lists to be submitted and approved by the health authorities before a distribution or activity can take place. This would not be possible within the window for early action for Typhoon. The technical working group in the country, which combines stakeholders of anticipatory action (Red Cross, FAO, WFP, Start Network) aims to raise the need for considerations for early action in a meeting in late June.

The capacity to act early in times of Covid-19 is not only influenced by travel restrictions etc. In many cases, organisations and authorities are stretched to the limit preparing for and responding to Covid-19, which means resources and attention to address other risks are diverted. In the recent floods in Uganda and Zambia, the National Societies did manage to share early warning information but could not act early on a larger scale because of restrictions on movement and because their attention was on Covid-19.

More than ever, the link to a network on the ground, like the Red Cross Red Crescent network of volunteers and branches or GNDR’s local member organisations, is essential to understanding the changing risks and to navigating operational and logistical challenges. In many cases, while mobility from the capital to communities at risk is restricted, travel within provinces or regions is possible. In the case of Bangladesh during cyclone Amphan, district branches had previously been trained by the German Red Cross’ and Bangladesh Red Crescent Society’s FbF project and had been supported with local grants from the American Red Cross, which meant they could implement the planned early actions with minimal travel from the headquarter. The Philippines Red Cross is also counting on its local chapters to carry out early actions if a trigger is hit in the coming weeks, as it is unclear whether travel from Manila will be possible. Recent workshops with the local Red Cross chapters raised many questions to the headquarter, but thanks to previous trainings and simulations, most chapter representatives felt confident they will be able to act without the additional support from HQ that was initially planned.

When Cyclones and COVID19 collide: Pandemic proofing Early Action Protocols

How can actions be adapted to minimize the risk of increasing Covid-19 transmission? In Bangladesh, the national government’s Cyclone Preparedness Programme (CPP) and Bangladesh Red Crescent Society (BDRCS) have given this a lot of thought. Even before Cyclone Amphan was approaching, CPP had released adapted guidance with the title: “Combating Cyclones in Covid-19 environment: Modified Cyclone Preparedness & Response Plan.” The plan encourages staff and volunteers to change the dissemination of EW messages, avoiding person to person contact, and instead using public announcements and mass communications tools like community radio and electronic media. The plan also suggests combining early warning messages with Covid-19 prevention and protection messages.

During Cyclone Amphan, these guidelines were put to the test. BDRCS and CPP had identified about 5700 additional shelters (by using schools and government buildings) to reduce density in shelters and ensure physical distancing to the extent possible. Disinfection gels, soap, and water were available in the shelters, and hand washing was encouraged. Volunteers received PPE and beneficiaries were encouraged to cover their faces with scarfs and lung is if lacking other materials. Suspected Covid-19 cases were accommodated in separate buildings. Despite restrictions, the BDRCS teams managed to assist 35900 evacuees through the Early Action Protocol activation, providing water and food and helping the most vulnerable families also bring their livestock and belongings to safety.

There is no reliable data yet as to whether the large-scale evacuations – in total the Bangladesh government evacuated more than 2 million people – led to an increase in Covid-19 infections. Infection numbers in the country have risen since landfall of Cyclone Amphan, however, it is difficult to get data per district. Most new cases seem to be registered in capital Dhaka, where there were no evacuations, but this could be influenced by availability of tests.

Our risk management work cannot be put on hold during Covid-19, even though organisations are stretched to the limits. It is critical to start thinking now about what would be done if we receive a forecast of an extreme event.

The following are some recommendations that emerged from our recent experiences and discussions on acting early in times of Covid-19:

- Discuss with authorities what restrictions would apply to humanitarian assistance and how these restrictions could be adapted to allow for early action when an extreme event is approaching. Find out beforehand which authorities will decide what actions are allowed at the community level.

- Get in contact with local branches and chapters on what support, training, or equipment they might need to be able to act without external support during an activation. While opportunities for trainings are currently restricted, remote advice can be helpful and transport of equipment and goods might still be possible.

- Determine which actions to take given Covid-19 risks. Which actions are necessary and why? Should the threshold for deciding to act be raised to the very extreme events? These discussions should involve the different stakeholders concerned.

- Assess how early actions need to be adapted to consider compound risks, mitigate the risk of Covid-19 infection, and take into account operational and logistical challenges due to Covid restrictions. Look at available guidance or discuss possibilities with other practitioners of anticipatory humanitarian action. Besides the before-mentioned guidance of UNDRR in Asia and CPP in Bangladesh, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has elaborated guidelines for preparing for hurricanes and evacuating in a Covid-19 context. The Climate Centre and the Global Heat Health Information Network have also published a checklist on managing heat risk during the Covid-19 pandemic.

About the author: Stefanie Lux is the Lead of the German Red Cross’ Anticipation Unit

[1] Forecast-based-Financing releases funding automatically, when forecasts indicate that an extreme event with severe humanitarian impacts is very likely. The forecast thresholds or triggers, the early actions to mitigate the humanitarian impact and the budget are pre-agreed and validated in so-called Early Action Protocols and funded by the IFRC’s FbA by the DREF once a trigger is reached.

- WMO Member:

- Bangladesh