Executive Council honours IMO laureate Timothy Palmer

The IMO Prize (named after WMO’s predecessor, the International Meteorological Organization) is the equivalent of a Nobel prize for meteorologists. It was established in 1955 and symbolizes the advancements that have been made in meteorology over the years.

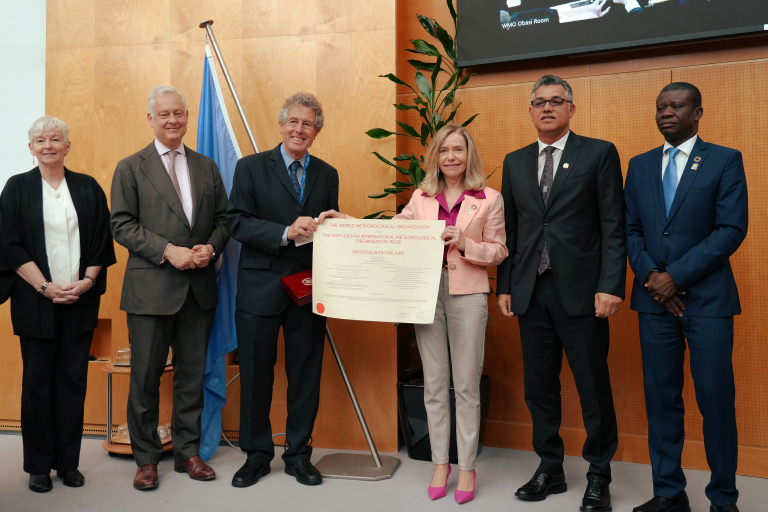

“This is the highest scientific award of WMO, to reward outstanding work in meteorology and hydrology and contributions to international collaboration in these fields,” said WMO President Abdullah Al Mandous.

In his acceptance speech, Mr Palmer traced his role in the development of probabilistic ensemble prediction methods for forecasting on all timescales.

With an eye on the future, he also highlighted how Artificial Intelligence is a potential game-changer for weather forecasts and long-term climate predictions. He argued that to meet the challenges and opportunities, it was vital to pool resources and develop kilometer-scale models.

“Timothy Palmer has demonstrated remarkable qualities over the years. His scientific ideas, skills, and abilities have had, and continue to have, a huge impact on the weather and climate fields,” said WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo.

Mr Palmer was nominated in 2023 and collected his award at a ceremony during WMO’s Executive Council meeting.

Ensemble forecasts

He is is a Professor Emeritus at the University of Oxford. He started his career as a lecturer and moved to the UK Met Office. He led the team that developed the world’s first ensemble prediction system at the UK Met Office for intra-seasonal forecasting.

From 1986 to 2011 he worked with the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecast (ECMWF) to lead the development of their medium-range ensemble forecast system. Ensemble models run multiple simulations from slightly varied initial conditions or using different model physics. They are valuable for medium to long-range forecasts (five to fifteen days) and are used to assess the confidence in a forecast by looking at the agreement among ensemble members.

At the time, there was still heavy reliance on deterministic models, which provide a single forecast for a given set of initial conditions, for a specific location and time.

The importance of ensemble models suddenly came to the fore when the UK was hit by the worst storm in centuries in October 1987, with hurricane-force winds which were not forecast because of the unpredictable, chaotic nature of the storm.

“Mother nature gave us the trump card,” said Mr Palmer. The ECMWF team re-ran retrospectively the ensemble system we had developed for this case which did indeed show a likelihood of hurricane-force winds – which were until then virtually unknown in the UK.

“This convinced people of the value of developing ensemble predictions,” he recalled.

Ensemble prediction is an almost universally used in weather prediction today, on all timescales. Developing reliable ensembles lies at the heart of many weather service strategic plans.

Importantly it is completely transforming the way in which disaster relief agencies operate.

“In the past agencies would only send in emergency food medicine and shelter after an event hit. The reason why they didn’t act preemptively was because deterministic forecasts were so unreliable,” said Mr Palmer.

Ensemble forecast allow humanitarian agencies to decide on a probability level for an extreme event. When this threshold is exceeded, it triggers anticipatory action, allowing financial resources and vital supplies to be sent in advance. Improving ensemble systems will be vital to make society more resilient to the new extremes of weather associated brought about by climate change.

“For me this is one of the greatest things that I feel proud of that this has had an impact on such an important area of humanity,” said Mr Palmer.

Artificial Intelligence

Mr Palmer has also been a tireless advocate of seamless weather and climate prediction.

He said the sudden advent of AI in 2023 was an “unanticipated shock,” but one which now offered huge potential. “We have an interesting new player on the block.”

Some AI systems are becoming competitive with ensemble models. Exactly how well they perform in the event of extreme weather situations is yet to be fully analysed.

Mr Palmer argued that regional meteorological services should start moving away from using limited area models to using AI-based downscaled forecasts based on global model ensembles. This would be comparably cheaper and more efficient. Work has begun with national meteorological services in Ethiopia and Kenya to introduce this scheme in their forecasts in Africa, he said.

To be able to compete with commercial forecast providers, Global Numerical Weather Prediction Centres should pool resources, he said. “From a science perspective, we do not need to maintain multiple models from different centres to represent model diversity. This is holding back progress.”

If physics-based models are to be competitive with AI models, we have to develop kilometer-scale Numerical Weather Prediction models – to be combined with AI methods.

Many recent extreme events, including the extreme heatwave in Canada (with temperatures of about 50°C) in 2021, the flooding in Pakistan in 2022, and persistent drought in southern Africa were “off the scale” for existing models, he said.

“We need to developing kilometer-scale models which we need for weather forecasting and climate predictions. It’s how we organize ourselves as an international community and how we interact and collaborate,” he said.

Mr Palmer has recently published a popular book “The Primacy of Doubt” emphasising the role of chaos and ensemble forecasting not only in weather and climate (where many of the ideas originated) but in economic and pandemic modelling, neuroscience and in fundamental physics.