2019 set to be 2nd or 3rd warmest year on record

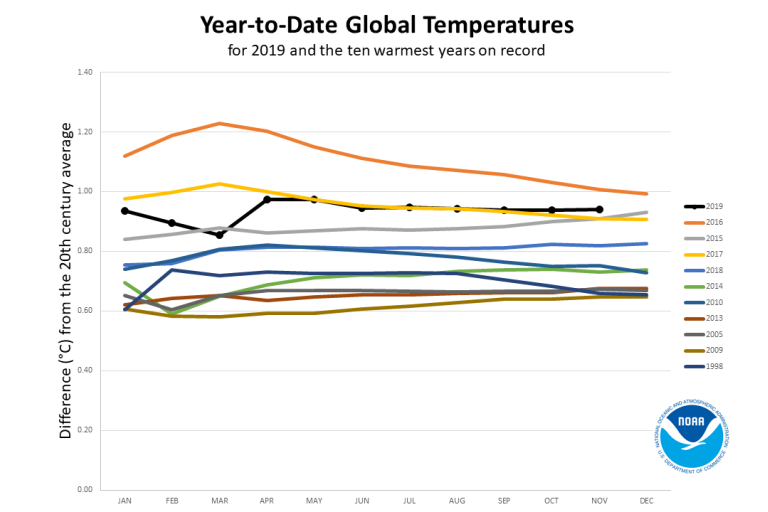

As 2019 draws to a close, it remains on track to be the second or third warmest year on record. The final ranking will be confirmed in January by the World Meteorological Organization, which consolidates leading international temperature datasets.

More important than the ranking of any one individual year is the long-term warming trend. Average temperatures for the five-year (2015-2019) and ten-year (2010-2019) periods are almost certain to be the highest on record. Since the 1980s each decade has been warmer than the previous one. This trend is expected to continue because of record levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Temperatures are only part of the story. The past decade has been characterized by retreating ice, record sea levels, increasing ocean heat and acidification, and extreme weather. These have combined to have major impacts on the health and well-being of both humans and the environment, as highlighted by WMO’s Provisional Statement on the State of the Global Climate in 2019, which was presented at the UN Climate Change Conference, COP25, in Madrid. The full statement will be issued in March 2020.

“The average global temperature has risen by about 1.1°C since the pre-industrial era and the ocean by half a degree,” WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas told the high-level segment of COP25.

The Arctic continues to melt and we have seen a boost in the melting of Greenland ice sheet which contributes to sea level rise in the southern hemisphere. Changes in the Arctic have an impact outside the Arctic in terms of cold patterns and heatwaves in the northern hemisphere.

We have broken records in the three main greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide. CO2 is the most important of these. We are heading towards a temperature increase of 3 to 5 degrees Celsius by the end of century,” Mr Taalas said.

January-November highlights

Figures released by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration showed that January-November was the second hottest such period on record (behind 2016). The September to November season and the month of November were also the second hottest on record (behind 2015). Temperatures in late 2015 and early 2016 were fuelled by an exceptionally strong El Niño. This was not the case in 2019.

The Copernicus Climate Change Service operated the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts said that globally, November 2019 was one of the three warmest Novembers on record, differing only marginally from November 2015 and 2016.

The world’s five hottest Novembers have all occurred since 2013.

Warming of the ocean continued: The world’s average sea surface temperature ranked second warmest for the year to date — just 0.05 of a degree F (0.03 of a degree C) cooler than the record-breaking year of 2016, according to NOAA.

Sea-ice coverage shrank to its second-lowest size on record for November in both the Arctic and Antarctic behind that observed in November 2016. Arctic sea ice coverage was 12.8 percent below the 1981–2010 average, while the Antarctic coverage was 6.35 percent below average.

In the annual Arctic Report Card, issued 10 December, NOAA said that the Arctic marine ecosystem and the communities that depend upon it continue to experience unprecedented changes as a result of warming air temperatures, declining sea ice, and warming waters.

The Greenland Ice Sheet is losing nearly 267 billion metric tons of ice per year and currently contributing to global average sea-level rise at a rate of about 0.7 mm yr-1.

Thawing permafrost throughout the Arctic could be releasing an estimated 300-600 million tons of net carbon per year to the atmosphere.

Wildlife populations are showing signs of stress. For example, the breeding population of the ivory gull in the Canadian Arctic has declined by 70% since the 1980s.

Indigenous Elders from Bering Sea communities note that "[i]n a warming Arctic, access to our subsistence foods is shrinking and becoming more hazardous to hunt and fish. At the same time, thawing permafrost and more frequent and higher storm surges increasingly threaten our homes, schools, airports, and utilities."