WMO Update: Prepare for El Niño

El Niño and La Niña conditions are associated with the biggest variation in the Earth's climate system on seasonal to annual timescales and can impact weather and climate across the globe. These conditions alternate in an irregular cycle called the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO for short.

The likelihood of El Niño developing later this year is increasing, according to a new update from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). This would have the opposite impacts on weather and climate patterns in many regions of the to world to the long-running La Niña and would likely fuel higher global temperatures.

The unusually stubborn La Niña has now ended after a three-year run and the tropical Pacific is currently in an ENSO-neutral state (neither El Niño nor La Niña).

There is a 60% chance for a transition from ENSO-neutral to El Niño during May-July 2023, and this will increase to about 70% in June-August and 80% between July and September, according to the Update, which is based on input from WMO Global Producing Centres of Long-Range Forecasts and expert assessment.

At this stage there is no indication of the strength or duration of El Niño.

“We just had the eight warmest years on record, even though we had a cooling La Niña for the past three years and this acted as a temporary brake on global temperature increase. The development of an El Niño will most likely lead to a new spike in global heating and increase the chance of breaking temperature records,” said WMO Secretary-General Prof. Petteri Taalas.

According to WMO’s State of the Global Climate reports, 2016 is the warmest year on record because of the “double whammy” of a very powerful El Niño event and human-induced warming from greenhouse gases. The effect on global temperatures usually plays out in the year after its development and so will likely be most apparent in 2024.

“The world should prepare for the development of El Niño, which is often associated with increased heat, drought or rainfall in different parts of the world. It might bring respite from the drought in the Horn of Africa and other La Niña- related impacts but could also trigger more extreme weather and climate events. This highlights the need for the UN Early Warnings for All initiative to keep people safe,” said Prof. Taalas.

No two El Niño events are the same and the effects depend partly on the time of year. WMO and National Meteorological Hydrological Services will therefore be closely monitoring developments.

Typical Impacts

El Niño is a naturally occurring climate pattern associated with warming of the ocean surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. It occurs on average every two to seven years, and episodes usually last nine to 12 months.

El Niño events are typically associated with increased rainfall in parts of southern South America, the southern United States, the Horn of Africa and central Asia.

In contrast, El Niño can also cause severe droughts over Australia, Indonesia, and parts of southern Asia.

During the Boreal summer, El Niño’s warm water can fuel hurricanes in the central/eastern Pacific Ocean, while it hinders hurricane formation in the Atlantic Basin.

Global Seasonal Climate Update

El Niño and La Niña are major – but not the only - drivers of the Earth’s climate system.

In addition to the long-established ENSO Update, WMO now also issues regular Global Seasonal Climate Updates (GSCU), which incorporate influences of the other major climate drivers such as the North Atlantic Oscillation, the Arctic Oscillation and the Indian Ocean Dipole.

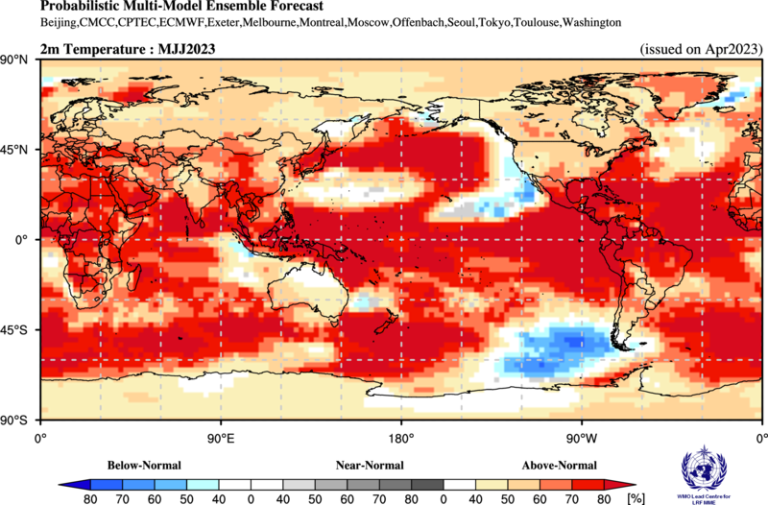

“As warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures are generally predicted over oceanic regions, they contribute to widespread prediction of above-normal temperatures over land areas. Without exception, positive temperature anomalies are expected over all land areas in the Northern and Southern Hemisphere,” says the latest update.

The WMO ENSO and Global Seasonal Climate Updates are based on forecasts from WMO Global Producing Centres of Long-Range Forecasts and are available to support governments, the United Nations, decision-makers and stakeholders in climate sensitive sectors to mobilize preparations and protect lives and livelihoods.

The tercile category with the highest forecast probability is indicated by shaded areas. The most likely category for below-normal, above-normal and near-normal is depicted in blue, red and grey shadings respectively for temperature, and orange, green and grey shadings respectively for precipitation. White areas indicate equal chances for all categories in both cases. The baseline period is 1993–2009.

Recent developments

From February 2023 onwards, there has been a significant increase in sea surface temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific, with notably stronger warming along the coast of South America.

As of mid-April 2023, the sea surface temperatures and other atmospheric and oceanic indicators in the central-eastern tropical Pacific are consistent with ENSO-neutral conditions. In the atmosphere, convective activity over the equatorial Pacific near the date line is near normal.

It is worth noting, however, that the Northern Hemisphere 'spring predictability barrier' a period characterized by somewhat lower predictive skill, has not yet passed. Nevertheless, these recent developments in oceanic and atmospheric conditions in the tropical Pacific, along with current predictions and expert assessments, are indicating a strong likelihood of El Niño onset in the early second half of 2023, and its continuation during the remainder of the six-month forecast period.

Notes to Editors

The WMO El Niño/La Niña Update is prepared through a collaborative effort between the WMO and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI), USA, and is based on contributions from experts worldwide, inter alia, of the following institutions: Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BoM), Centro Internacional para la Investigación del Fenómeno El Niño (CIIFEN), China Meteorological Administration (CMA), Climate Prediction Centre (CPC) and Pacific ENSO Applications Climate (PEAC) Services of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the United States of America (USA), European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), Météo-France, India Meteorological Department (IMD), Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), International Monsoons Project Office (IMPO), Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA), Met Office of the United Kingdom, Meteorological Service Singapore (MSS), WMO Global Producing Centres of Long Range Forecasts (GPCs-LRF) including the Lead Centre for Long Range Forecast Multi-Model Ensemble (LC-LRFMME).

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for promoting international cooperation in atmospheric science and meteorology.

WMO monitors weather, climate, and water resources and provides support to its Members in forecasting and disaster mitigation. The organization is committed to advancing scientific knowledge and improving public safety and well-being through its work.

For further information, please contact:

- Clare Nullis WMO media officer cnullis@wmo.int +41 79 709 13 97