Rate and impact of climate change surges dramatically in 2011-2020

Geneva/Dubai (WMO) - The rate of climate change surged alarmingly between 2011-2020, which was the warmest decade on record. Continued rising concentrations of greenhouse gases fuelled record land and ocean temperatures and turbo-charged a dramatic acceleration in ice melt and sea level rise, according to a new report from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

- 2011-2020 was warmest decade on record

- Glacier and ice sheet loss unprecedented

- Sea level rise accelerates

- Ocean heat and acidification damage marine ecosystems

- Extreme weather undermines sustainable development

- Ozone layer on track to recovery

The Global Climate 2011-2020: A Decade of Acceleration sounded the alarm, in particular, at the profound transformation taking place in Polar regions and high mountains. Glaciers thinned by around 1 meter per year - an unprecedented loss – with long-term repercussions for water supplies for many millions of people. The Antarctic continental ice sheet lost nearly 75% more ice between 2011-2020 than it did in 2001-2010 – an ominous development for future sea level rise which will jeopardize the existence of low-lying coastal regions and states.

In a glimmer of hope, the report said that the Antarctic ozone hole was smaller in the 2011-2020 period than during the two previous decades thanks to successful and concerted international action to phase out ozone depleting chemicals, an indication of the success of the Montreal Protocol.

“Each decade since the 1990s has been warmer than the previous one and we see no immediate sign of this trend reversing. More countries reported record high temperatures than in any other decade. Our ocean is warming faster and faster and the rate of sea level rise has nearly doubled in less than a generation. We are losing the race to save our melting glaciers and ice sheets,” said WMO Secretary-General Prof. Petteri Taalas.

“This is unequivocally driven by greenhouse gas emissions from human activities,” said WMO Secretary-General Prof. Petteri Taalas. “We have to cut greenhouse gas emissions as a top and overriding priority for the planet in order to prevent climate change spiralling out of control,” he said.

“Our weather is becoming more extreme, with a clear and demonstrable impact on socio-economic development. Droughts, heatwaves, floods, tropical cyclones and wildfires damage infrastructure, destroy agricultural yields, limit water supplies and cause mass displacements,” said Prof. Taalas. “Numerous studies show that, in particular, the risk of intense heat has significantly increased in the past decade.”

The report documents how extreme events across the decade had devastating impacts, particularly on food security, displacement and migration, hindering national development and progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

But it also showed how improvements in forecasts, early warnings and coordinated disaster management and response are making a difference. The number of casualties from extreme events has declined, associated with improved early warning systems, even though economic losses have increased.

Public and private climate finance almost doubled between 2011 and 2020. However, it needs to increase at least seven times by the end of this decade to achieve climate objectives.

The report was released at the UN Climate Change Conference, COP28, and emphasizes the need for much more ambitious climate action to try to limit global temperature rise to no more than 1.5°C above the pre-industrial era.

The Decadal State of the Climate report provides a longer-term perspective and transcends year-to-year variability in our climate. It compliments WMO’s annual State of the Global Climate report. The provisional annual report for 2023, released at COP28, said that 2023 is set to be the warmest year on record.

The report is based on physical data analyses and impact assessments from dozens of experts at National Meteorological and Hydrological Services, Regional Climate Centres, National Statistics Offices and United Nations partners.

Key Findings:

It was the warmest decade on record by a clear margin for both land and ocean.

Global mean temperature for the period 2011-2020 was 1.10 ± 0.12 °C above the 1850-1900 average. This is based on the average of six data sets used by WMO. The warmest six years on record globally were between 2015 and 2020.

Each successive decade since the 1990s has been warmer than all previous decades.

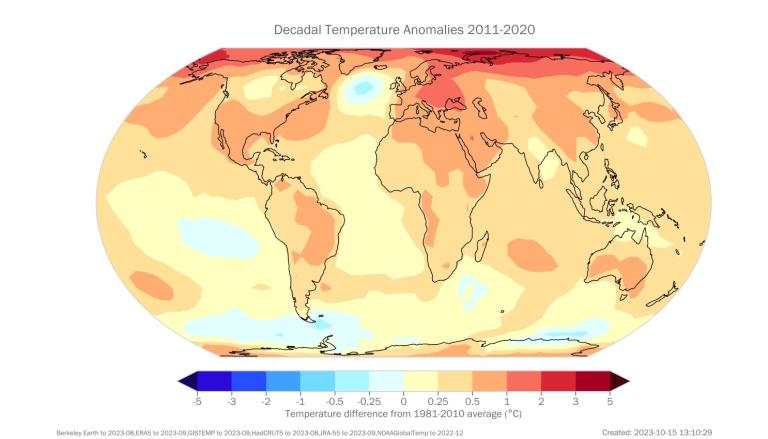

The warmest years of the decade were 2016, because of a strong El Niño event, and 2020. The largest positive anomalies for the decade, in places more than 2 °C above the 1981-2010 average, were in the Arctic.

More countries reported record high temperatures than in any other decade.

Atmospheric concentrations of the three major greenhouse gases continued to increase over the decade.

For about 10,000 years before the start of the industrial era, atmospheric carbon dioxide remained almost constant at around 280 ppm (ppm=number of molecules of the gas per million molecules of dry air). Since then, CO2 has increased by nearly 50% reaching 413.2 ppm in 2020, primarily due to the combustion of fossil fuels, deforestation, and changes in land-use.

The decadal global average CO2 during 1991-2000 was 361.7ppm, during the decade 2001-2010 it was 380.3 ppm, while in 2011-2020 it rose to 402.0 ppm.

During the same periods the average growth rate increased from 1.5 ppm/yr and 1.9 ppm/yr to 2.4 ppm/yr.

In order to stabilize the climate and prevent further warming, emissions must be sustainably reduced.

Rates of ocean warming and acidification are increasing.

Around 90% of the accumulated heat in the Earth system is stored in the ocean. Ocean warming rates show a particularly strong increase in the past two decades.

Ocean warming rates for the upper 2000m depth reached rates of 1.0 ± 0.1 Wm-2 over the period 2006-2020, compared with 0.6 ± 0.1 Wm-2 over the full 1971-2020 period. It reached a record high in 2020 and it is expected that this trend will continue in the future.

A consequence of the accumulation of CO2 in the ocean is its acidification, namely a drop in the oceanic pH, which makes it more challenging for marine organisms to build and maintain their shells and skeletons.

Marine heatwaves are becoming more frequent and intense.

In any given year between 2011 and 2020, approximately 60% of the surface of the ocean experienced a heatwave.

The three years having the highest average of days with marine heatwaves were 2016 (61 days), 2020 (58 days), and 2019 (54 days).

Marine heatwaves have become relatively more intense in the most recent decade. Category II (Strong) events have become more common than those rated in Category I (Moderate). There was an average of 0.5 day extreme marine heatwave (Category IV) per year in the past decade, with 1 full day in the El Niño year 2016. In the past these extreme events – which can change entire ecosystems - were so uncommon that they could hardly be measured on a global scale.

Global mean sea level rise is accelerating, largely because of ocean warming and the loss of land ice mass.

From 2011 to 2020, sea level rose at an annual rate of 4.5mm/yr. This compares with 2.9 +/- 0.5mm/yr in 2001-2010.

Global mean sea level rise has accelerated, mostly due to a speeding up of ice mass loss from the Greenland ice sheet, and, to a lesser extent, due to accelerated glacial melting and ocean warming.

Glacier loss is unprecedented in the modern record.

Glaciers that were measured around the world thinned by approximately 1m per year on average between 2011 and 2020.

The latest assessment based on 42 reference glaciers with long-term measurements reveals that the period between 2011 and 2020 saw the lowest mean mass balances of any observed decade. Some of the mass balance reference glaciers have already melted away, as the winter snow nourishing the glacier melts completely during the summer months.

Nearly all the 19 primary glacier regions have witnessed increasingly large negative values from 2000 to 2020.

The remaining glaciers near the Equator are generally in rapid decline. Glaciers in Papua, Indonesia are likely to disappear altogether within the next decade. In Africa, glaciers on the Rwenzori Mountains and Mount Kenya are projected to disappear by 2030, and those on Kilimanjaro by 2040.

Greenland and Antarctica lost 38% more ice between 2011 and 2020 than during the 2001-2010 period.

The Greenland and Antarctic continental ice sheets are the largest freshwater reservoirs on Earth, storing a volume of 29.5 million km3 of frozen water. When ice sheets lose mass, they directly contribute to raising the global mean sea level and, therefore, monitoring the volume of ice they gain or lose is critical to assessing sea level change.

During the 2011-2020 decade, Greenland lost mass at an average rate of 251 Gigatonnes (Gt) per year and reached a new record mass loss of 444 Gt in 2019. The Antarctic continental ice sheet lost ice at an average rate of 143 Gt yr- during this decade, with more than three-quarters of this mass loss coming from West Antarctica. Compared to the previous decade (2001-2010), this represents an increase of nearly 75% in ice losses. This is not the same as Antarctic sea ice.

For the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets combined, there was an increase of 38 % in ice losses compared to 2001-2010. It confirms the sustained increase in losses compared to the 1990s (1992-2000), when Greenland and Antarctica ice sheet losses amounted to 84 Gt yr.

Arctic sea ice extent continues a multi-decade decline: the seasonal mean minimum was 30% below average.

Arctic sea ice continued to decline, particularly during the summer melt season. The mean seasonal minimum extent during the 2011-2020 period was 4.37 million km2, 30% below the 1981-2010 average of 6.22 million km2. The decrease was less pronounced, but still substantial, during the winter accumulation season, with an annual mean maximum during the decade of 14.78 million km2, 6% below the 15.65 million km2 average for the 1981-2010 period.

Reduced sea ice extent was accompanied by a decrease in thickness and volume, although data for these indicators are more limited. There has also been a marked decrease in the extent of ice which lasted for more than one year. In March 1985, old ice (four years or more) accounted for 33% of the total ice cover of the Arctic Ocean, but that figure had fallen below 10% by 2010, and in March 2020 it had dropped to 4.4%.

The ozone hole was smaller in the 2011-2020 period than during the two previous decades.

On average, over the 2011-2020 period, the annual maximum mass deficit was lower than during the previous two decades. Due to the actions taken under the Montreal Protocol, the total amount of chlorine entering the stratosphere from controlled and uncontrolled Ozone Depleting Substances (ODSs) such as Chlorofluocarbons (CFCs) declined by 11.5% from its peak value of 3660 ppt in 1993, to 3240 ppt in 2020.

Total ozone values in the Antarctic are projected to return to 1980 values by around 2065. Total springtime ozone is expected to return to 1980 values in the Arctic by approximately 2045.

Sustainable Development

In order to achieve the SDGs and meet the targets of the Paris Agreement, there is need for synergistic action, whereby advancements in one can lead to improvements in the other.

For the very first time, this report demonstrates concrete connections between extreme events and development. Working in interdisciplinary collaboration with United Nations agencies and National Statistics Offices, select case studies demonstrate how extreme events across the decade have impeded progress toward the SDGs.

Extreme events across the decade had devastating impacts, particularly on food security and human mobility. Weather and climate-related events were responsible for nearly 94% of all disaster displacement recorded over the last decade, and played a role in the backward trend in the progress of global efforts to end hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition.

For many extreme events, the likelihood of an event of that magnitude has been altered, often greatly, because of anthropogenic climate change. Virtually every attribution study found that the likelihood of an extreme heat event increased significantly.

Heatwaves were responsible for the highest number of casualties, while tropical cyclones caused the most economic damage.

The number of casualties from extreme events has declined, associated with improved early warning systems, but economic losses have increased.

A major contributor to this decrease has been improved early warning systems, driven by improvements in forecasting, coupled with improved disaster management. The 2011-2020 decade was the first since 1950 when there was not a single short-term event with 10,000 deaths or more.

However, economic losses from extreme weather and climate events have continued to increase. While Hurricane Katrina in 2005 remains the world’s most costly weather disaster, the next four most costly events were all hurricanes that occurred in the 2011-2020 decade, and whose greatest impacts were in the United States and/or its territories.

There was great contrast between events causing large numbers of casualties and those incurring great economic losses, both in terms of the type of event and their geographic distribution. Of the 13 known events resulting in more than 1000 deaths, six were heatwaves; four were monsoonal flooding or landslides associated with such flooding, and three were tropical cyclones.

Of the 27 events with known economic losses exceeding 10 billion US dollars (USD), in 2022, 16 occurred within the United States and eight in East Asia; 13 of the 27 events were tropical cyclones, eight floods and three wildfires.

The World Meteorological Organization is the United Nations System’s authoritative voice on Weather, Climate and Water.

For further information, please contact:

- Clare Nullis WMO media officer cnullis@wmo.int +41 79 709 13 97

- WMO Strategic Communication Office Media Contact media@wmo.int