Heat and drought bite in large parts of South America

Large parts of Argentina and neighboring countries have been reeling under drought conditions. These have combined with heatwaves to fuel wildfires and accelerate glacier melt, harming local communities and economies, ecosystems and agriculture.

Although climate change is not solely responsible, it is aggravating the impacts.

Since 2019 large parts of Argentina and neighboring countries have been reeling under drought conditions with the last four months of 2022 receiving less than half of the average precipitation: the lowest rainfall in 35 years.

Combined with high temperatures, this has led to widespread crop failures. Argentina is one of the world’s top wheat exporters but agricultural exports for 2023 are projected to further drop 28% compared to 2022 levels. Uruguay declared an agricultural emergency in October 2022, with 60% of the country’s territory experiencing “extreme” or “severe” drought.

Scientists from Argentina, Colombia, France, the United States of America, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the low rainfall that led to drought, focussing on the particularly severe three months from October to December 2022.

The World Weather Attribution rapid analysis concluded that climate change was NOT the main driver of the reduced rainfall. However, it also showed that climate change increased temperatures in the region, which probably reduced water availability and worsened the impacts of drought.

The region is also experiencing intense heatwaves, which climate change has increased in frequency, intensity and duration. In a recent study conducted in an overlapping area, World Weather Attribution scientists found that human-induced climate change made extreme temperatures in December 2022 about 60 times more likely.

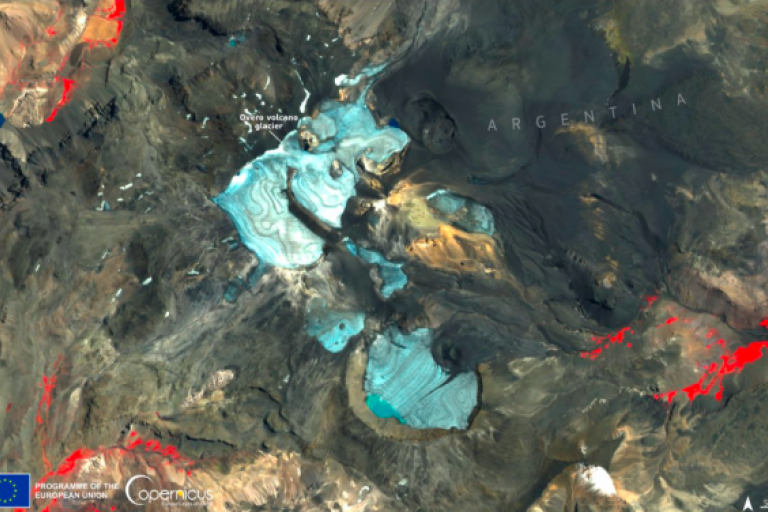

Argentina experienced its warmest November-January on record and is now enduring its eighth heatwave of the season, according to Argentina’s National Meteorological Service. This has fuelled devastating fires in central Argentina, and also neighboring Chile, melting Andean glaciers, harming air quality and sending smoke plumes across the Pacific.

Central Chile’s Mega Drought has lasted more than 13 years, according to WMO’s latest State of the Climate in Latin America report. This constitutes the longest drought in this region in at least one thousand years, exacerbating a drying trend and putting Chile at the forefront of the region’s water crisis.

A likely important factor in the low rainfall is that South America is currently experiencing the effects of a third consecutive year of La Niña, a naturally occurring phenomenon with major influence on climate patterns in various parts of the world, including the increased likelihood of lower rainfall in many parts of this region.

WMO will issue its next El Niño/La Niña and Global Seasonal Climate Update by the end of February.