Antarctic heat, rain and ice prompt concern

Record high temperatures, rain and the collapse of an ice shelf in East Antarctica have prompted questions and concern about the possible role of climate change in the coldest and driest part of the world.

Record high temperatures, rain and the collapse of an ice shelf in East Antarctica have prompted questions and concern about the possible role of climate change in the coldest and driest part of the world.

The events happened just after Antarctic sea ice minimum extent after the summer melt fell below 2 million square kilometers (772,000 square miles) for the first time since satellite records in 1979, according to the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center.

The Antarctic climate and sea ice extent is subject to big natural variations from year to year and are influenced by the high winds in this remote part of Earth which spans 14 million km2 (roughly twice the size of Australia). The average annual temperature ranges from about −10°C (14°F) on the Antarctic coast to −60°C (-76°F) at the highest parts of the interior.

The Antarctic Peninsula (the northwest tip near to South America) is among the fastest warming regions of the planet, almost 3°C over the last 50 years. Remote East Antarctica, by contrast, has until now been less impacted.

However, in the third week of March, research stations in East Antarctica recorded unprecedented temperatures.

For example, Vostok in the middle of the ice plateau hit a provisional high of -17.7℃ (0.14°F), smashing the previous record of -32.6℃ (-26.68°F). The Russian station, at 3420 meters altitude, has the world’s official lowest temperature record of -89.2°C (-128.6°F), according to WMO’s Weather and Climate Extremes Archive.

Dome Concordia (Dome C), an Italian-French research station also on the high plateau, experienced its highest ever temperature for any month, which was about 40℃ above the March average.

“The warm temperature at Dome C, still much below freezing, is probably more a wake up call, not having significant local impact in the inner ice sheet. On the other hand, the fact that the temperature was way above 0°C and that it rained at the coast upstream the previous day is more of a concern. Rainfall is rare in Antarctica but when it occurs, it has consequences on ecosystems - particularly on penguin colonies - and on the ice sheet mass balance,” commented Etienne Vignon and Christoph Genthon, who are both from France’s Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique, IPSL/Sorbone Université/École Polytechnique/CNRS UMR 8539, Paris, and experts of the WMO Global Cryosphere Watch.

“Fortunately there are no longer penguin chicks at this time of the year but the fact that this happens now in March is a reminder of what is at stake in the peripheral regions: wildlife, stability of the ice sheet. Here the warm temperature at Dome C is a source of excitement for climatologists, that it rains at the coast in March is a source of concern for everyone,” said the experts, who are both from France’s Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique, IPSL/Sorbone Université/École Polytechnique/CNRS.

The warmth and moisture was driven primarily by an atmospheric river – a narrow band of moisture collected from warm oceans. Atmospheric rivers are found on the edge of low pressure systems and can move large amounts of water across vast distances.

“This event is rewriting record books and our expectations about what is possible in Antarctica. Is this simply a freakishly improbable event, or is it a sign of more to come? Right now, no one knows,” tweeted Dr Robert Rohde, Lead Scientist at Berkeley Earth.

Scientists says it is too soon to say definitively whether climate change is the cause.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report on the Physical Science Basis – part of its ongoing Sixth Assessment Report - said that: Observations show a widespread, strong warming trend starting in the 1950s in the Antarctic Peninsula. Significant warming trends are observed in other West Antarctic regions and at selected stations in East Antarctica (medium confidence).

“Antarctica has often been referred to as a “sleeping giant” … it’s the coldest, windiest and driest continent and often thought of as being relatively stable. However recent temperature extremes and ice shelf collapses have reminded us that we shouldn’t take Antarctica for granted. The Antarctic ice sheets hold almost 60 meters of potential sea level rise. Understanding and properly monitoring the continent is therefore crucial for society’s future well-being," said Dr Mike Sparrow, head of the WMO co-sponsored World Climate Research Programme.

The increased frequency of extreme temperatures highlights the importance of reliable observations from stations operated by parties to the Antarctic Treaty. There are significant challenges to obtaining quality continuous measurements over the surface of Antarctica. For that reason, WMO is committed to strengthen expertise and cooperation via its Global Cryosphere Watch network to improve observations and instrumentation.

Ice sheet

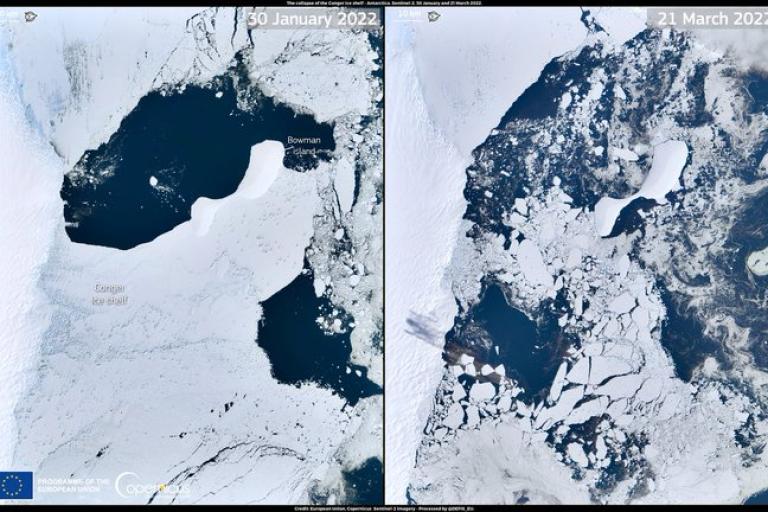

Just ahead of the heatwave, East Antarctica’s Conger ice shelf – a floating platform the size of Rome or New York City – broke off the continent on March 15, 2022. Its collapse was caught on satellite.

It is too soon to say what triggered the collapse of the Conger ice shelf, but it appears unlikely to have been caused by melting at the surface. Since the beginning of satellite observations in the 1970s, the tip of the shelf had been disintegrating into icebergs in a series of what glaciologists call calving events.

Although it is relatively small in size, and unlikely to have any global significance, the collapse of the ice shelf was another warning sign.

“As glaciologists, we see the impact of global warming on Antarctica in increasing ice loss with time. And what happens in Antarctica does not stay in Antarctica,” according to an article in the Conversation by Hilmar Gudmundsson, Professor of Glaciology and Northumbria University, Adrian Jenkins, Professor of Ocean Science, Northumbria University, Newcastle, and Bertie Miles, Leverhulme Early Career Fellow, Geosciences, University of Edinburgh.

“Global warming is making events like this more likely. And as more and more ice shelves around Antarctica collapse, ice loss will increase, and with it global sea levels …. Not everything that happens in nature is due to global warming alone. Antarctica loses mass through the discharge of icebergs and waxing and waning ice shelves as part of a natural cycle. But what we are seeing now, with the collapse of the Conger ice shelf and others, is the continuation of a worrying trend whereby Antarctic ice shelves undergo area-wide collapse one after another,” they wrote.

Both major ice sheets – Greenland and Antarctica – have been losing mass since at least 1990, with the highest loss rate during 2010–2019 (high confidence), and they are projected to continue to lose mass, according to the IPCC.

As a result of the melting of the ice sheets and glaciers, the rate of global sea level rise has increased since satellite altimeter measurements began in 1993, reached a new record high in 2021, according to WMO’s provisional report on the State of the Global Climate in 2021. The final report will be published early May.

The Antarctic ice sheet is up to 4.8km thick and contains 90% of the world’s fresh water, enough to raise sea level by around 60 metres were it all to melt.